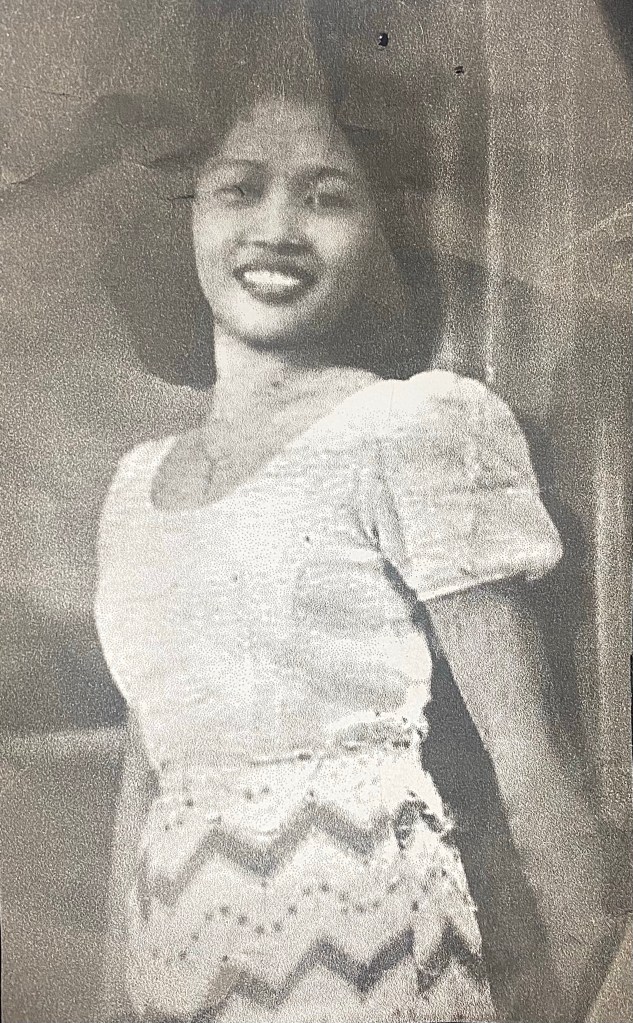

She was born in Carigara, Leyte in The Philippines in 1932. Or 1930. Her birth records were destroyed during WWII so she was able to rewrite her story in the way that suited her best. The almost total destruction that was her home country gave her a clean slate with which to start her life as a survivor. Carigara is a small town on the coast of Carigara Bay, in the 30’s it was a small village. She once told a story about playing on the beach and climbing the coconut trees. I have no reason to think her life was anything but idyllic. That was until 1938 when her beloved father died unexpectedly.

She so loved him. Memories of him came back to her often, whereas memories of her mother were much harder to grasp. I have always thought it was because the pain connected to her father was his death. The pain connected to her mother was of the war. For at least part of the time, my mother and grandmother were together in Manila during the war years. Memories of her mother had to be buried as deeply as other memories of the darkest years that any human could endure.

The light that was her life before leaving Leyte gave her father the path he needed to find her after his death. He made frequent visits to her during her life in America. It was he who came to take her “home” when she died in 1993. Two weeks before her death she said to me, as we sat, just the two of us, waiting for the doctor, “My Dads here. Want to meet him?” And she turned her head and started speaking to the unseen presence in the room. Speaking in a language I did not recognize. Perhaps it was the language of her childhood village. No, I did not experience his presence at the time.

She was 9 when the war started. She was outside of the home they lived in in Cavite, on the shores of Manila Bay. The home her mother moved them to after the death of her father. She heard the first Japanese fighters as they flew in over Manila Bay and turned north, to Clark Airfield on December 8, which was December 7 on the other side of the International Dateline. She was almost 13 years old when it ended. Puberty during a World War.

I can’t imagine her life during the war. I dedicated a part of my life to learn about how the war played out for the civilians but there is very little information in the history books written by the American hand. There are volumes of first hand accounts from the European theatre, but very little from the Pacific arena. Perhaps there was less concern for how Asians dealt with Asians.

Some can be gleamed from flipping through the books about the American experience in World War 2 Philippines. Filipinos loved the American servicemen. There was no reason not to. They were the good guys. There to fight alongside the Filipino freedom fighters. My mom remembered being given a candy bar by one of the good guys. So different from the treatment the natives received from the occupying Japanese Army. Most particularly during the Battle for Manila in February of 1945.

My mother was in Manila during the siege that took place in February and into March of 1945. The horrific atrocities attributed to the Japanese Army rival the stories that came of Nanking, China. The Filipino people were left to starve as the Imperial Army took anything and everything that could be eaten. Stories of babies tossed in the air and caught in the tips of bayonets. Men forced to watch as the wives, mothers, and daughters were gang raped, or object raped. Women’s bodies who were broken during those unspeakable acts. People who hid under the piles of the dead that lined the streets to avoid a patrolling Japanese platoon. The streams of spilled Filipino blood that ran down the streets to the Pasig River. The estimate of Filipino casualties during the monthlong battle range from 100,000 to 240,000. Not sure why the range is so very great. One can only surmise that the American government didn’t feel it important enough to narrow it down. What’s 140,000 Filipino lives, give or take.

Medical care for non Army personnel during a war was kind of catch as one can. Locals who knew something of how to care for wounds became the “doctors”. Neighbors who treated their children before the war became who everyone went to see when the weight of war became too much for bodies to bear. Especially the young ones. My mom suffered from dysentery, a prolapsed rectum, malaria, starvation, mumps, as well as entering into puberty.

She watched her mother succumb to a “wasting disease” but without medical care one can only guess what that disease was. My mom knew her older brother was shot in the head. She was with her baby brother as he died, most likely from another illness that could have been treated with access to care. She watched as the bodies of her mother and little brother were thrown into separate pits along with all the other dead because there are no funerals in time of war.

The war scars ran deeper than even she knew. There is no measure for gauging what life should have been as opposed to what it was. With the exception of memories of her father which she so clearly set aside and used them as a shield of comfort, all she knew of childhood was war. The largest, most destructive war the world has ever known was the backdrop for my mother’s formative years. The effects of which would be handed down for generations to come.

Leave a comment